I said “no.” I declined an opportunity that theoretically, maybe, someday, would prove to be good for me and good for my community. And it was painful, even though the stakes were low. Did I do something wrong? Should others’ disappointment give me pause? Should I reconsider my decision? Saying no is indeed a hard thing to do.

All of this mental noise motivates me to send a message to the world, and it’s a message that’s hard to communicate. But it needs to be said. In any profession, perhaps especially in the nonprofit space, we have terrible incentives to say no, even when we know it’s the right thing to do.

Much of what I say here is informed by my own experience in eighteen years of professional work with those who serve one particular kind of nonprofit: denominational churches in the United States. Countless conversations with pastors, staff, and volunteers have informed my viewpoint about the benefits, as well as the perils, of saying yes to new ventures. While much of what follows is geared toward nonprofits and their employees, I also include a short guide for freelancers because so many of us fall into both categories. I hope it helps you create a structure around important decisions you inevitably have to make.

Why It Sucks to Say No

The reason it feels so terrible to decline an opportunity is because our brains are hard-wired for the pleasurable, comforting feelings we associate with saying yes. We also operate in a culture where most workplaces, from C-level administration to hourly desk workers, incentivize saying yes to everything. Just look really, really busy and you’ll get ahead eventually.

Reasons to say “yes”:

- Building new relationships is one of your strongest sources of job security—or so you assume. You gradually make yourself indispensable, one “yes” at a time.

- You receive an immediate emotional reward, because you have soothed your fear of missing out (FOMO) on something that might be unexpectedly great.

- You avoid the emotional penalty of saying “no,” because you avoid the risk of disappointing others.

- There is often some kind of financial incentive, either now or later.

- It is easy. It is the default answer and follows the typical script of human interaction. Too many “yesses”? That’s tomorrow’s problem.

Reasons to say “no”:

- You protect time to continue working on what you already know is important, thus achieving better results on your stated priorities. This is absolutely the number one reason to say “no.”

- You preserve the opportunity to say “yes” to projects or initiatives that might be even more beneficial to yourself and the world.

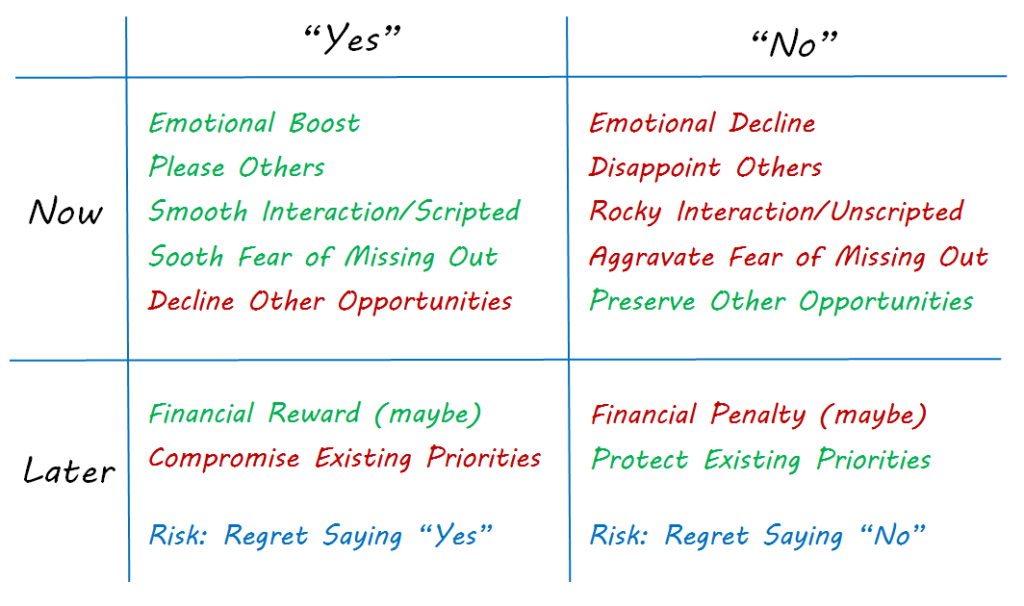

Here is a useful way to summarize the perils of “yes” versus “no.”

I hope this says it all. Most of the penalties for saying “no”—social, emotional, and financial—come right away, and most of the rewards for saying “yes” are just as immediate. No wonder we tend to overcommit! Note that I included the risk of later regret in both columns in a neutral color, because there will always be that risk. Thus, I try to avoid taking it into account when the consequences of saying “no” are reversible. New opportunities will come around again in due course, and you’ll one more have the chance to say “yes.”

What we need is a reliable pathway for deciding it’s OK to say “no,” because we don’t do it nearly often enough. What follows is my attempt to offer one such pathway to the world of nonprofits, and by extension, anyone who cares about their line of work.

For Bosses and Employees

As a friend once told me, “there are so many ways to be a bad boss, and so few ways to be a good one.” I can’t think of a truer statement. If you are in any position of authority, recognize that anyone who works for you will become less and less effective the more “yesses” you force upon them. If you can’t accept that consequence, prepare for a revolt (or just bad results). I’m aware of only one way out of this problem, and that is to clearly communicate priorities. What can your assistant/secretary/employee do less of to make room for new projects?

The same advice goes for employees. Your job description, which you agreed to when you were hired, requires you to say “yes” to a large number of things, and sometimes you end up over your head. Instead of floundering in a sea of stress, present a list of your projects to your boss and ask him/her which is the most important. The answer will guide your focus and help you ignore distractions. It’s much better to be effective at one thing than lousy at many.

If your supervisor regularly tells you that all of your projects are of equal importance, and you aren’t allowed to negotiate deadlines, they are setting you up for failure. If they can’t accept this inevitable failure, you need to find another job. Or keep this one at a great risk to your long-term health.

For Nonprofit Teams

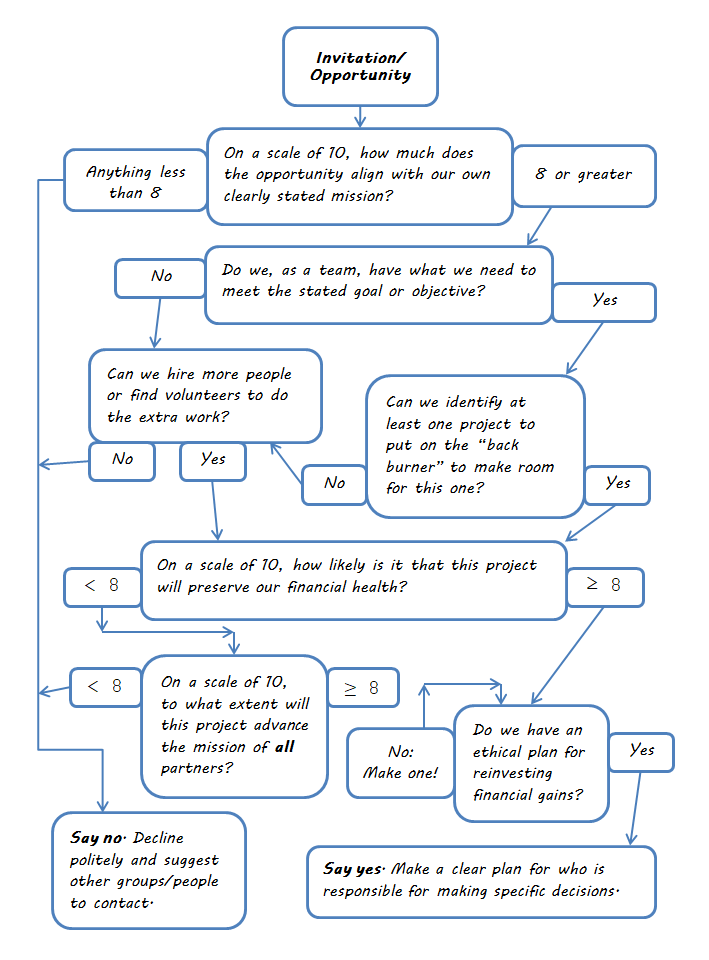

Sometimes a team, such as a nonprofit board, is presented with an opportunity to partner with similarly aligned organizations, or to “spin off” a new nonprofit with a different focus. More than a moment’s introspection is required here, because the consequences of a bad partnership can be disastrous. To make things easier, I put together a little flow chart (one of my favorite things in the world).

Two things should immediately jump out at you. One is the great number of paths to “no” in comparison with the relatively few possible paths to “yes.” The other is the rigorous “eight out of ten” standard. The reason I have forced you to clear such a high bar is because the planning fallacy leads us to overestimate the actual value and impact of a proposed project, and to underestimate the burden it will place on existing resources. So if you find yourself with a 7-out-of-10, that’s not nearly strong enough to justify compromising other projects that are 8’s and higher.

I imagine that some of you will take issue with this from a purely philosophical standpoint, because at first glance it looks like a “zero-sum” argument. But it actually isn’t, as long as you can expand your resources (time and money) by recruiting new labor (paid or unpaid) to the effort. The chart takes these possibilities into account.

For “Solo-preneurs” and Freelancers

“We can’t pay you what you’re worth, but I think it will be a good opportunity for you to gain some exposure and network with new people.”

How many times has someone told you some version of this? The freelance world is full of genuinely valuable opportunities that fall in this category, and it’s an all-too-familiar refrain for anyone who regularly accepts freelance work. In most creative fields, the supply of labor far exceeds the demand for our services, which means that it sometimes makes sense to work for free, or for a dramatically reduced rate. The trouble is that many of these opportunities turn out to be a complete waste of time. I want to suggest one method that might help you separate the wheat from the chaff. If you can prune the unruly shrub of professional life, you will find space for even better opportunities.

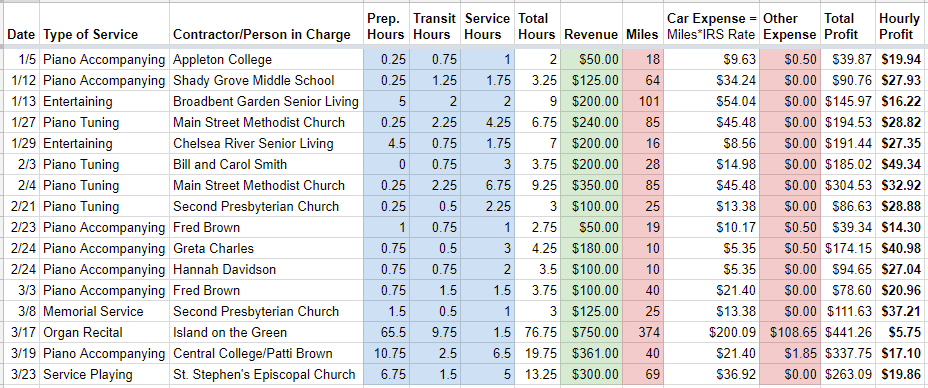

Take the following chart for example. I’ve modified some of the details for the sake of illustration, but the type of information included here is exactly what I use in my own records.

Besides the obvious conclusion that freelancers have to charge a lot more than $20 per hour to actually earn $20 per hour, this chart can guide you to other valuable insights. Which type of work brings you the greatest fulfillment? Which type of work is the most financially profitable? My hope is that you will discover a happy convergence between these two questions: which kinds of work satisfy both tests? My hope is that this answer will guide your decisions about which opportunities to accept and which to decline.

On the subject of declining opportunities, by the way, you should note that this chart only includes the freelance work I accepted. I also use the formulas in this chart to draw up hypothetical calculations for proposed work opportunities, and ultimately to decline those that don’t line up with my career goals or my financial needs. For example, I was recently offered a gig that paid something like $50 per call, for a total paycheck between $400 and $500. I plugged a few numbers into the spreadsheet, taking into account all of the time spent preparing for the gig, the time “in service” on site, time spent behind the wheel of my car, and all related expenses. After three minutes of number crunching, I discovered that the total commitment equaled a full time workweek and more, amounting to a profit of less than $10 an hour, all for a type of work that I don’t particularly love. I knew that I either needed to negotiate a higher fee (which was unlikely to be successful in this case because they were hiring a dozen or more contractors at the same time) or say “no.” See how easy the decision became once I had some clear data on hand?

The Upshot (TL;DR)

Everyone struggles with saying “no” because our brains punish us for it. We live in a world that rewards us for looking busy, whether or not we actually achieve our goals. Fortunately, with objective methods for making decisions—both at the institutional and individual levels—we can achieve greater clarity about which opportunities are truly worth the effort they require. Used judiciously, the word “no” is a great tool you can use to improve productivity and focus for yourself and your organization.

This article was originally published on April 3, 2018 at linkedin.com.

For more articles like this one, check out the Church Music Sense blog.

What do you think? Leave a reply.