How many times have you struggled to find great choral music for your church? You have so many limitations to consider. Your choir doesn’t learn difficult music quickly, so you can’t program old masterworks every week (if ever). Your existing library has a bunch of anthems in roughly the same style. And so much of what’s out there is so thoroughly mediocre.

Finding choral music you’ll love is certainly possible—and easier than ever with new resources available all the time. (Stay tuned for a future post about these!) But if you really want a program filled with variety, creativity, and fun, you need to learn how to weed out the stuff that won’t work. Quickly.

With that in mind, here are four tell-tale signs that you’re looking at a lemon.

Weak Text

Why not start off with the fastest way to eliminate choices from the pool? Weak texts are surprisingly easy to identify once you’ve divorced them from the music that illuminates them. Simply put, a weak text sounds fine when set to beautiful music, but fails to stand on its own when read aloud by itself. This is the number one sign that you’re looking at bad choral music. After all, how good of a piece can it be if the text was clearly an afterthought?

Weak Text Red Flags

Here are a few red flags you can identify quickly. One or two shouldn’t immediately disqualify anything, but I’d be concerned if you find several of these in the same piece.

- Words and music by the same person. Not all composers are poor authors, and not all authors are poor composers. But the composition of poetry and prose require just as much practice as the composition of music. Composers who write their own texts are much less likely to produce texts that consistently stand on their own. And if they do succeed in writing a great text, they probably won’t succeed in writing the best music to go with it. I’m betting you’ll find this to be the case more often than not when the same person writes both.

- Dubious use of scripture. It is usually obvious when the author has paraphrased a bible passage beyond recognition. Less obvious is the more common practice of interjecting personal commentary. But I’m betting you’ll find it when you read the text aloud.

- Excessive “I” or “we” language. There is a fine line between illuminating scriptural teachings versus simply telling us how we should feel or what we should do. Both are necessary, and I’m betting you’ll find it easy to identify which texts go too far.

- Lack of form. Music lends itself naturally to clear formal design. One common form found in both music and poetry is A-B-A or ternary, which involves three self-contained sections with clear similarity between the two ‘A’ sections. Thus poetry in A-B-A form lends itself naturally to musical settings of the same construction. Read the poetry or prose by itself and see if you can identify a clear form.

- Indiscriminate mixture of style. Is the text colloquial or formal? Flowery and decorative, or minimal and economical? There is no such thing as the “wrong” style of text, but keep in mind that the more the author mixes styles, the more difficult it will be to set the text to a three- to five-minute piece of music. Music does not switch from one mood or style to another as easily as text.

Summary

Paul Rardin of Temple University says it best. In his view, a good text is distinctive, challenging, and moving; it does not merely act as “a vehicle for the music.”1

Range Confused with Tessitura

The choral music most appropriate for volunteer choirs avoids extremes of range, the overall upper and lower pitch limits for each part. For example, you won’t see many low C’s for the basses or high A’s for the sopranos, because amateur voices tend not to sound their best at these extremes. Most commercially published works get this right, in part because it is easy for an editor to identify at a glance whether or not a composer has violated this guideline.

Range is not at all the same thing as tessitura, the general “zone” of pitches where most of the notes lie in the voice. This is a subtle but critical distinction. It is relatively easy to ensure that the altos never sing above a high D (the upper range limit). It is much more difficult to write an alto part that sits in the right part of the voice (the comfortable tessitura). What’s more, the “right” part of the voice varies by age, ability, and even nationality (because different cultures and languages employ different registers of the voice).

Too many composers fail to recognize this distinction. To illustrate, here is a tenor part from Edgar L. Bainton’s And I Saw a New Heaven:

At first glance, you might be concerned that the part extends all the way to g’, a high note indeed for many amateur singers. But suppose that in an attempt to address this, Bainton opted for this instead:

Problem solved, right? No more F#’s and G’s. The trouble is, now you have a part that sits right in the middle of the amateur tenor’s most uncomfortable range: a little too low for falsetto to sound any good, and little too high for relaxed, healthy tone. (This version is also perilously boring compared to what Bainton actually wrote.)

Summary

Range is not necessarily a reliable indicator for whether a piece will be accessible for amateur voices. Instead, the discriminating director should always consider questions of both how often and for how long each voice part sustains notes at the extremes of their range. The occasional high note is surprisingly easy when placed in the right context.

Inconsistency in Place of Variety

Composers writing for amateur musicians tend to simplify the music to the extent it is musically desirable. This is a good instinct, but it sometimes creates a piece that is simplified to the point of boredom. Realizing this, composers will sometimes “engineer” variety back into the music by slightly changing elements that repeat (chiefly pitch and rhythm).

Suppose you have a hymn anthem based on “Abide with Me.” The first and second appearances of the tune appear as follows, copied verbatim from the original:

Suppose that now, for a little variety, we change a rhythm and a few pitches:

This creates variety, but now we have two different melodies for essentially the same tune. Are these changes really different enough to justify the effort required to remember the difference? Without any particular imperative set by the text, I would argue no. The opening quarter rest is enough to trip up an unsuspecting singer. As a director, I’d much rather focus my efforts toward other challenges.

Placing the melody in the tenor would be no more difficult to harmonize, and would avoid the problem of almost-sameness:

Summary

Good compositions simplify the rhythm enough to make it accessible for the amateur singer, but without introducing arbitrary complexity. Paradoxically, if a given passage is going to differ from what came before it, it needs to be different enough.

Notation and Engraving Bugaboos

I include this as a bonus category. Though notation and engraving are not strictly musical considerations, they do carry significant weight in a director’s programming decisions. And they should!

Many directors anticipate questions, taking “evasive action” by annotating the written score in advance of the first rehearsal. This way, the rehearsal doesn’t get bogged down in tedious questions about what the singers are supposed to do.

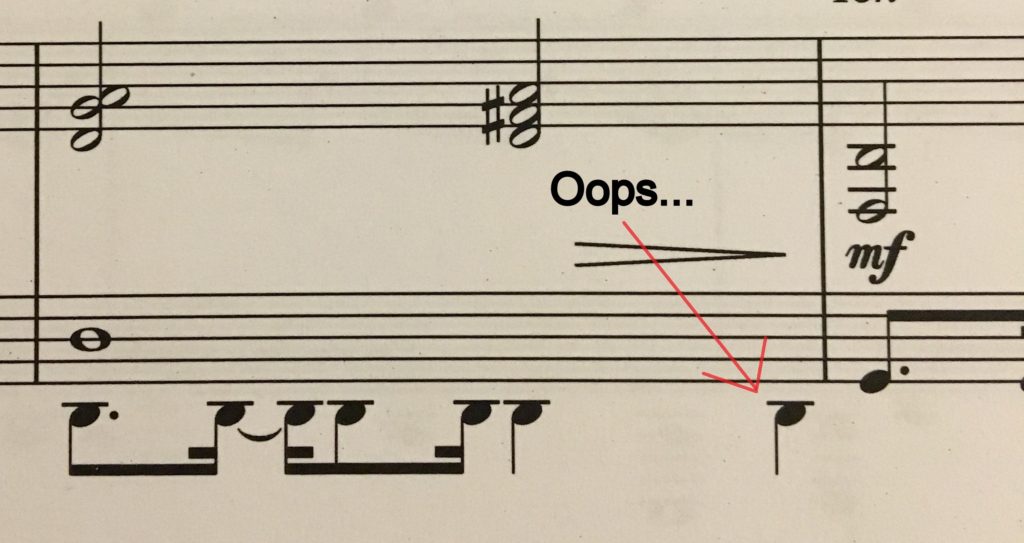

So what happens when you’re confronted with a score that’s infected with frustrating errors, confusing instructions, and mashed-up engraving? You probably decide it’s not worth your trouble, no matter how much you like the music itself.

Here are a few examples of what to look for:

- Way too much music crammed onto a single page

- Notes and/or text printed too small for viewing at an arm’s length

- Spacing errors (notes too close together or too far apart in relation to the actual rhythm)

- Beams, ties, and rests applied inconsistently

- Collisions (these are obvious)

…And so on. To its credit, mainstream publishing understands the needs of its market, and as a result, it has mostly solved these problems. It usually succeeds in fixing notation and engraving errors before the music goes to press. But this of course doesn’t help you at all with scores that are already in print. Look out!

Summary

A good score clarifies the composer’s expectations for the performer, with a minimum of errors that take focus away from the music itself. Think twice before you program an otherwise good piece with an awful score. (I’ve made that mistake too many times, and regretted it deeply.)

Wrap-Up

Bad choral music is quite unfortunately easy to find. But if you know the warning signs, you can steer clear of the worst offenders. No single trait should disqualify a piece from your library, but the four I’ve outlined here—weak text, range confused with tessitura, inconsistency in place of variety, and notation and engraving bugaboos—are reliable enough indicators to warrant your attention.

What do you think? Leave a reply.